When most people think of publishing, they imagine a writer being paid for their work, an editor polishing it, and a reader buying the final product. This transactional loop, however imperfect, makes a certain kind of economic sense.

Academic publishing, however, doesn’t follow this pattern. In fact, it inverts it.

In academic publishing, it is not the publishers that pay those who work to generate the content, it is the other way round. Then there are also the reviewers, experts in their particular fields, who are called upon to assess and review the content submitted by the authors before publication, a process that can take months with a lot of back and forth. They also work pro bono. Meanwhile, the publishers profit by charging either the readers through subscriptions or, more recently, the authors themselves through article processing charges (APCs). The result is a system where the people who create and validate knowledge are volunteering their time, while the organizations that distribute it turn a handsome profit.

This would be strange enough if it were a quirky side effect of bureaucracy. But it’s not. It’s the system. And it’s wildly profitable.

The Economics of an Asymmetry

Producing a peer-reviewed paper is not a trivial affair. Researchers spend months, sometimes years, gathering and analyzing data, refining arguments, and engaging with an ever-growing thicket of academic literature. When they’re finally ready to publish, they often face hefty charges just to make their work publicly available. Article processing charges commonly range from $1,600 to $4,000, with high-prestige journals charging much more. Nature, for instance, now charges over $12,000 for its Gold Open Access option.

Even when authors manage to publish without paying upfront, usually in subscription-based journals, universities and libraries still foot enormous bills to access that content. This is what makes the economic structure so peculiar: the costs are real, but they are rarely borne by the publishers. Independent studies estimate that the actual cost of processing and publishing a paper lies somewhere between $200 and $700. The rest? Pure profit.

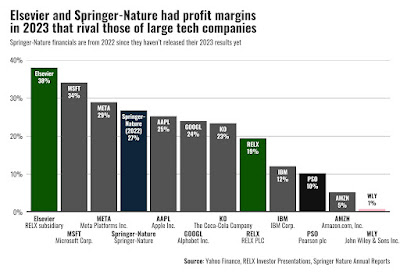

And profit they do. Elsevier reported a 38% operating margin in 2023, a number that surpasses even tech giants like Apple or Alphabet. Springer Nature and Taylor & Francis reported margins in the 28% range and 35% range respectively. These are not the returns of a struggling industry. They are the hallmarks of a rentier model built on monopolizing access to knowledge.

To add insult to injury, authors often surrender copyright to their own work. That means they can’t freely share, reuse, or even publicly post their own findings, at least not in the final, published form, without explicit permission from the publisher. The content is no longer theirs. It belongs to the distributor.

Open Access: A Solution That Isn't

But what about Open Access journals? At first glance, Open Access seems like the fix we’ve all been waiting for: make all research freely available to everyone, no subscriptions, no gatekeeping. Knowledge for the many, not the few. And indeed, perhaps that was the intention, to remove paywalls and democratize access to scientific findings. But Open Access has not solved the problem. It has simply moved it.

Instead of charging readers or libraries to access research, publishers now charge authors to publish it. These are the aforementioned Article Processing Charges, often thousands of dollars per article, paid by researchers, their institutions, or more often, indirectly by the public through government-funded grants. So the cost hasn’t disappeared. It’s just been shifted upstream. The reader no longer pays, the writer does. And the writer’s wallet is frequently taxpayer-funded.

Meanwhile, the underlying business model remains intact. Publishers are still extracting massive profits, just from a different node in the chain. Worse, this system often introduces new barriers: now, if you want to publish in a prestigious journal, you don’t just need good ideas. You need funding. Researchers at underfunded institutions, in the Global South, or in fields with limited grant support, are once again priced out, not from reading the science, but from contributing to it.

The paywall hasn’t been demolished. It’s just been relocated.

The Oubliette

The academic publishing system persists because of an unspoken compromise between compliance and necessity. Academics know it’s exploitative, but early-career researchers are under immense pressure to publish in prestigious journals. For academics, especially early on in their careers, tenure, funding, credibility, it all hinges on where you publish, not just what you publish.

So even when researchers are aware of the flaws, they cannot afford to not participate. It’s not apathy. It’s survival. Change, under these conditions, is not just difficult. It can be professionally dangerous.

On Academic Duty

Defenders of the system sometimes argue that writing and peer review are part of the academic job, already paid for by salaries, grants, or public funding. Why not then consider peer review as a kind of civic duty? The problem is that this narrative overlooks the broader structure. First, academic salaries are modest, often significantly lower than those offered to individuals with comparable skills in industry. Most academics work on precarious contracts, with limited institutional support. Second, publicly funded research should be accessible to the public, not hidden behind paywalls that restrict its reach and impact. Third, tax money intended to support the advancement of science should not be diverted to enrich private publishing companies, but should instead be reinvested into further research and education. Fourth, the time and effort dedicated to peer reviewing and revising articles comes at the expense of teaching, mentoring, and conducting new research, core activities that universities and the public explicitly value.

Peer review is essential labor. Without it, the entire edifice of scholarly communication collapses. And yet it is invisible in tenure files, promotion cases, and annual evaluations. It is uncredited, unremunerated, and often thankless.

There are broader implications, too. High APCs and subscription costs deepen the divide between wealthy institutions and the rest of the world. Researchers in lower-income countries, or even underfunded departments, simply can’t afford to participate in this system, either as authors or readers. The result is a kind of epistemic inequality: knowledge flows downhill, access is tiered, and entire regions are locked out of the global scientific conversation.

Reform and Solutions

Given these inequities, it is clear that reform is needed. One promising model is exemplified by platforms like the Open Journal of Astrophysics, which uses the arXiv preprint server as its submission system. Here, articles are submitted openly and peer reviewers are assigned to evaluate the work transparently. This system minimizes costs, maximizes accessibility, and keeps ownership with the researchers. This model could be expanded. Universities and consortia could collaborate to host decentralized, nonprofit journals. These would restore control to the scholarly community and reduce dependence on commercial platforms.

Alternatively, the publishing industry could introduce a model where both authors and reviewers are remunerated for their contributions. Reviewers could receive base compensation for their evaluations, with opportunities to earn higher rates for thorough, well-argued, and respectfully conducted reviews. Outstanding reviewers could be recognized through formal credentials and higher pay rates, encouraging a culture of constructive and diligent peer review. Authors could also be provided with modest stipends to offset the hidden costs of article preparation and revisions. Such a system would not only reward academic labor fairly but also improve the overall quality, rigor, and civility of scholarly communication.

Such reforms wouldn’t just create fairer conditions. They’d likely improve the quality, speed, and rigor of scholarly communication as a whole.

Reclaiming the Commons

Researchers themselves also have a role to play in driving change. Before achieving tenure, they can carefully balance the need to publish in high-impact journals with efforts to also submit work to reputable, low-cost open-access venues whenever possible. They can advocate for transparency in peer review and promote discussions about reform within their institutions. After achieving tenure, researchers are in a stronger position to challenge the status quo more openly: by prioritizing low-cost open-access journals, participating in or founding new publishing initiatives, mentoring young researchers about their publishing choices, and pressuring academic societies and funding agencies to support open science principles.

And for those outside academia: this affects you too. As taxpayers, your tax money funds most of this research. You have a right to access it. You have a right to ask why the products of public investment are being locked away for private profit. You can support open-access legislation, pressure politicians to pressure funding agencies and universities to rethink publishing priorities, and back projects that are trying to do things differently. Journalists, educators, and policymakers can help raise awareness of the inequities in academic publishing. Ultimately, by demanding that publicly funded research remain publicly accessible, we can all help shift the system toward one that serves science and society, rather than private profit.

Knowledge as a public good

Academic publishing has become a system where the creators of new knowledge must pay to give it away, while the public, who funded the creation of this new knowledge, must pay again to read it. The costs are high, the profits concentrated, and the labor largely invisible.

If we believe that knowledge is a public good and not a luxury commodity, then we need to work towards a system that reflects that belief. That means rewarding the work that sustains it, reducing barriers to entry, and making the outputs of scholarship freely available to all.

The current structure is outdated. The incentives are misaligned. But the alternatives are no longer hypothetical. They’re real, viable, and already in motion.

All that remains is the will to choose them.

References:

Cost of publication in Nature https://www.nature.com/nature/for-authors/publishing-options

How publishers profit from article charges: https://direct.mit.edu/qss/article-pdf/4/4/778/2339495/qss_a_00272.pdf

How bad is it and how did we get here? https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/jun/27/profitable-business-scientific-publishing-bad-for-science

How academic publishers profit from the publish-or-perish culture

https://www.ft.com/content/575f72a8-4eb2-4538-87a8-7652d67d499e

Academic publishers reap huge profits as libraries go broke

The political economy of academic publishing: On the commodification of a public good

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0253226

Elsevier parent company reports 10% rise in profit, to £3.2bn

Taylor & Francis revenues up 4.3% in 'strong trading performance'

https://www.thebookseller.com/news/taylor--francis-revenues-up-43-in-strong-trading-performance